The Glimpse of Beauty That Changed Me

My mom's garden led to a lifelong search for that same magic.

For a long time my social media bio was “Working on the Internet now so I can live in the woods later.” Cringe, but sincere. I’ve always been reluctant to spend a life in front of a screen, and even when I was younger and my ambition was at full throttle, I never had any fantasies about moving to the Big City to live out a career-driven life. All I ever really wanted was to own all of my time and to use it to grow things and make delight.

I can trace it back to a core memory of being 10 years old in the backyard with my mom. She lived outside barefoot and wearing tattered gloves, always in a frenzy of digging and planting, weeding and composting. I was surprised one morning when she pointed out a section of her garden where I could plant something of my own. This was Mom’s special place. It was undulating with colors, teeming with life, and dominated by a gnarly old cherry tree.

She had made it all by herself. And it was one of the most beautiful things in the world, I believed.

A different core memory emphasized that impression. One Saturday after finishing my route delivering the Buffalo News in our starter-home neighborhood, I cycled past a kid from another school. I didn’t know him, but he followed me home hoping we might play. We let our bikes fall onto the driveway and walked around the garage to the back of the house. The sun was casting that lazy summer morning glow, and Mom’s garden dazzled in the dappled light like a kaleidoscopic projection. I realized I was viewing it through the eyes of this kid seeing it for the first time. I turned to see his face, and his mouth was gaping.

“You guys must be rich!” he blurted.

I knew we weren’t rich, but I let him think so. It wasn’t until decades later that I appreciated how keen his remark had been.

So when my mom suggested she could make room for me to have a garden of my own, I knew she was inviting me to something special. I vividly remember the first cucumber that emerged from a yolky-colored blossom on the vine she taught me to sow. I was truly astonished.

In some way, all I’ve ever done since is try to experience again the magic of that first cucumber.

But as you know, life happens, and you get sucked into things. I graduated college, moved to NYC to chase money, and began my long career staring at a screen and fantasizing about a life spent outside.

It was while I was feeling trapped in New York that I discovered Christopher Alexander. Few thinkers have practically influenced me as much as him. I was interested in his ideas about cities: that they’re valuable, but their continuous sprawl and the increasing disconnect between city-dwellers and the countryside are causing them to essentially become inhumane.

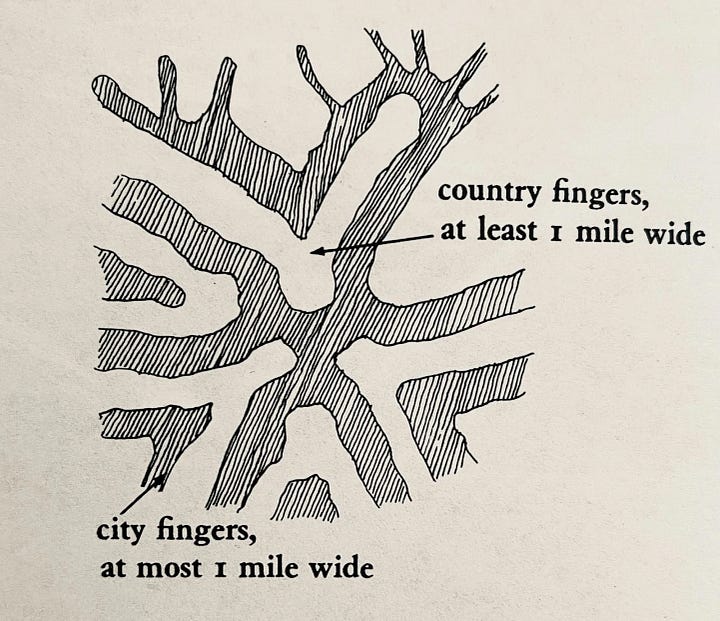

In his seminal book A Pattern Language, he suggested an ideal pattern of building cities he called City Country Fingers:

If we wish to re-establish and maintain the proper connection between city and country, and yet maintain the density of urban interactions, it will be necessary to stretch out the urbanized area into long sinuous fingers which extend into the farmland.

I believed this pattern to be impracticable at the scale he described—at least in the US, where we’ve ceased to seriously build cities—but the general idea of interlocking fingers of human ingenuity and natural splendor, of stimulation and retreat, of hard and soft, seemed like a pattern you could practice at any scale.

It was around then that I decided to move to San Francisco, a city that I consider one of the better American examples of an advanced economy interlaced with nature.

My newlywed wife and I picked the Mission District to search for a home. It ticked the most important box for any East Coaster moving to California: plenty of sunshine all year long. But what we liked most about it was its own interlocking fingers of Victorian townhouses and large warehouses converted to lofts, of light industry and cheerful elementary schools, of old railroad easements and coffee shops. Honestly, it mostly reminded us of home in Brooklyn.

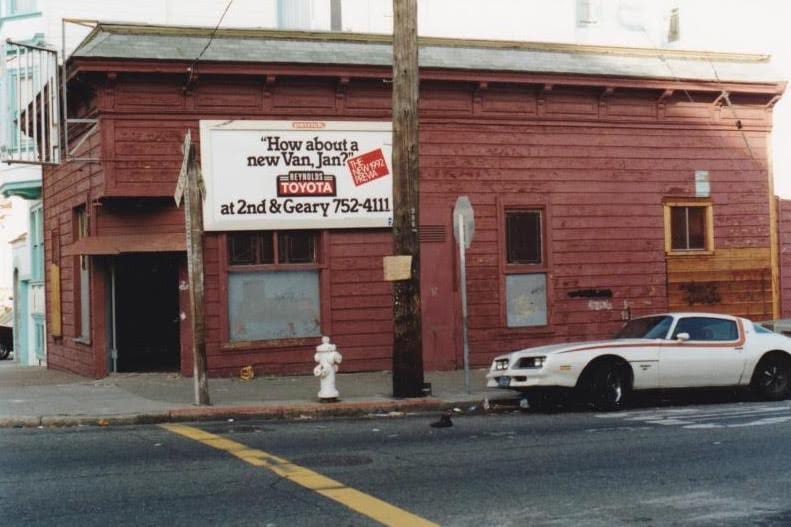

We knew we had found the perfect TLC project when we saw the For Sale sign on an unusual corner building. We later learned it had served most of its 120-year lifespan as a rundown bar, but at some point it had been rezoned to residential. It was just sitting there, empty and long unsold, waiting for someone to do the work to bring it up to code (that’s a different story; when we started the process we had zero kids and by the time we moved in we had two.)

What struck me about the surrounding blocks was another example of interlocking fingers: mostly treeless and neglected sidewalks varied with stretches where the concrete had been ripped out and replaced with mounds of succulents, yucca, and agave.

These little sidewalk gardens wormholed me back to that childhood backyard; I realized there were other growers nearby.

It didn’t take long to find Jane Martin. She was the force of nature behind many of the sidewalk transformations that I had stumbled upon. In fact, she alone had tenaciously coaxed the city to introduce a low-cost permit to allow homeowners to convert a portion of their sidewalk into landscapes.

Serendipity. She lived three blocks from me, and I asked her to teach me everything.

I learned that these gardens eliminate excessive hardscape and increase permeable landscape that absorbs storm water. They counter the urban heat island effect and regulate their block’s ambient temperature. And they grow San Francisco’s tree canopy, at that point only covering approximately 15% of the city’s area, which is relatively small when compared to cities like New York City (24%) and Seattle (30%). Most important to me, they give city kids (and adults!) something green to touch every day.

They are City Country Fingers at the DIY scale. We got to work on our own.

Our process started in 2013 when we asked Friends of the Urban Forest to help us plant two olive trees. They organize block planting events and coordinate all of the necessary permits, trees, and supplies. The trees we planted that day would later become critical for our garden's success by blocking gusty afternoon winds and providing shade to help other plants get established.

By 2016 the street trees had already established themselves. We proceeded with the demolition of the existing sidewalk, which was nearly 12 feet wide. The city allows you to plant much of that as long as you maintain a six-foot width of unobstructed path.

Most of our plants have one thing in common: drought resistance. Jane helped us with that. We also considered how nice they are to touch, as well as their ease of propagation (in case plants were stolen or failed to thrive on the first planting).

We waited for wet weather in January 2017 to plant. This pause allowed the plants to establish themselves in optimal conditions before weaning them off of watering. We also added stones to suppress weeds and trap moisture.

Today, ten years after being planted, the original street trees are nearly 25 feet tall, and in our small way we have disrupted the continuous urban sprawl.

The work never ends, and we continue to find ways to nourish it. We added lights connected to a photosensor to illuminate the path and help maintain a safe space at night. Last summer the kids and I used a kit to add a free book exchange.

The kids actually play a big part. They’re 8 and 10 now, and they’ve grown up in the garden. We spend nearly every weekend weeding and picking trash, making cuttings to fill in areas that have failed to thrive. My favorite part is when neighbors stop to comment on the garden and to thank us for the work. I’m pleased the kids are experiencing themselves as contributors to a wider community, where the barter can be as simple as doing what you love and receiving gratitude in exchange.

I hope this will be one of their core memories. Maybe their first cucumber.

All of this is in dedication to my mom, Kim Klein, the lifelong gardener who gave me many things, but nothing as important as her true passion. I’m also fortunate that I inherited her preference to be barefoot.

Mom passed away in 2017 at age 60. We miss her deeply and every day remember how she inspired us.

Get Involved

If you’re interested in a sidewalk garden of your own, I published a more technical document with tips, FAQs, and a complete plant list.

Wonderful! I didn’t know.

“i’m not crying you’re crying” 🪴