An Old Argument Returns

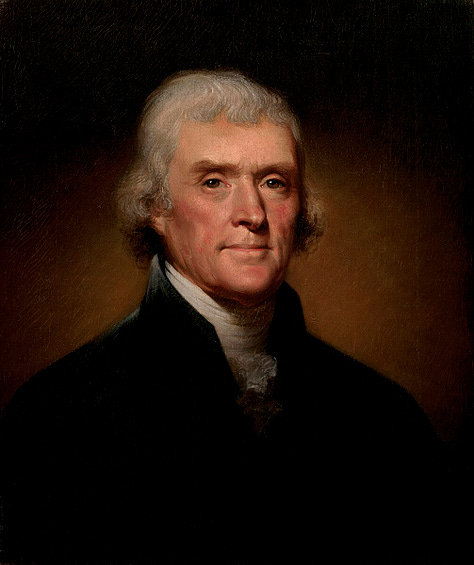

Can democracy grow anywhere? Simón Bolívar thought so and asked Thomas Jefferson for help more than 200 years ago ... Jefferson refused.

One of my favorite books of the last decade was The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf.

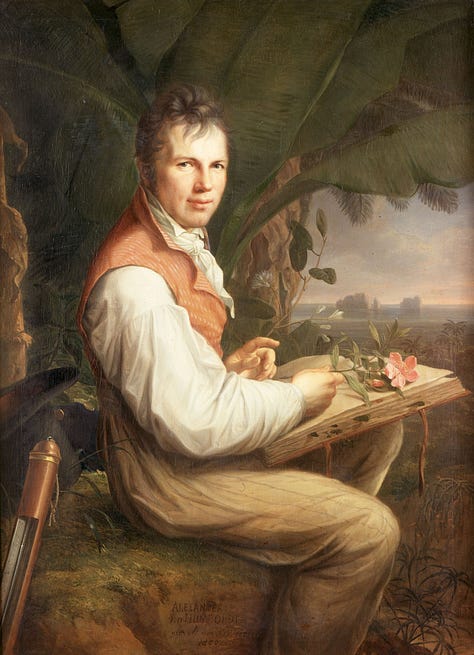

It’s a biography of Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), a Prussian naturalist virtually unknown to Americans (a fascinating rabbit hole related to anti-German sentiment during the World Wars). Humboldt's big idea was that nature is not a collection of parts, but a web, a web of ecological, social, and political systems that could not be understood in isolation.

I’ve been thinking about the book again this weekend because of the events in Venezuela.

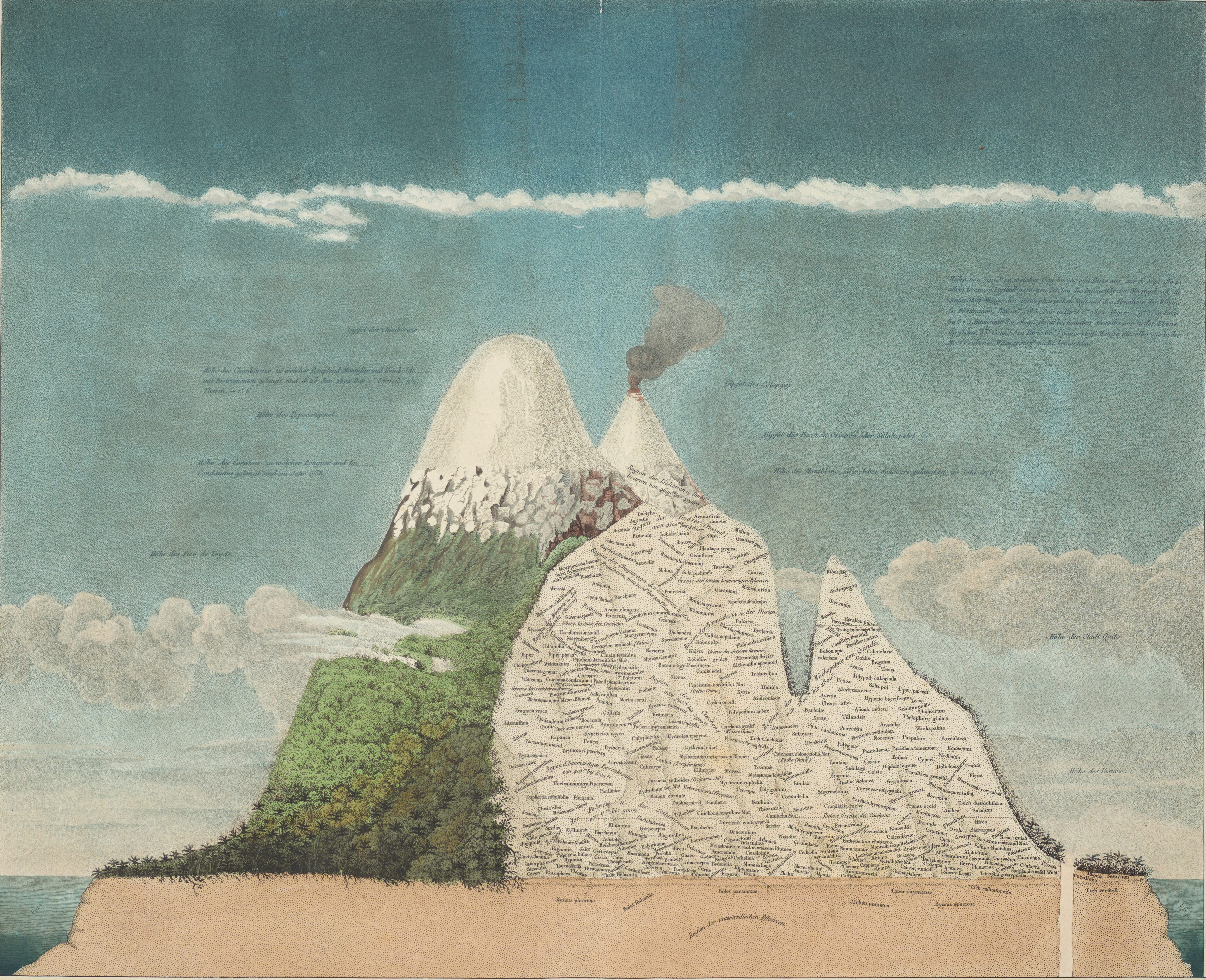

Humboldt traveled to South America between 1799 and 1804 with the aim of mapping the web. Largely self-funded, he moved through what is now Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, and Cuba, carrying an unprecedented array of scientific instruments to measure climate, altitude, magnetism, geology, and plant distribution. The continent offered an ideal laboratory: extreme variations in altitude and climate compressed into short distances allowed him to compare ecological systems vertically rather than across continents.

At the same time, Humboldt observed colonialism, slavery, and land use as forces acting directly upon natural systems. He was the first to link colonialism to environmental devastation and predicted human-induced climate change.

His years-long journey and related publications would impact North and South American history.

They provided the first rigorous statistical portrait of the Spanish Americas: population, agriculture, mining, trade, and taxation. Thomas Jefferson prized these measurements, as well as Humboldt’s maps, of the Americas as authoritative data for understanding the region that the United States sought to expand into and manage.

In contrast, a continent away, Simón Bolívar absorbed Humboldt’s work and was convinced that New Spain was economically viable and self-sustaining without a global power to administer it. Humboldt’s observations, he believed, were proof that geography did not limit political capacity.

Wulf describes the subsequent and extraordinary triangle of influence and correspondence between the three men and how their ideas converged, often uncomfortably, around this question.

In 1815, while in exile, Bolívar wrote directly to Jefferson, framing the South American independence movements as an extension of Enlightenment republicanism. He appealed to the United States not merely for recognition, but for moral solidarity. As the first successful post-colonial republic in the hemisphere, Bolívar believed the U.S. had an obligation to support democratic self-rule elsewhere in the Americas.

Jefferson’s response was cautious to the point of paralysis. While privately sympathetic to independence movements, he doubted that Spanish America was ready for democracy. This was astonishing revelation to me given the lengths he went to support the French Revolution.

His skepticism rested on arguments about geography, climate, and even Catholicism. These claims echoed the environmental determinism of the era.

Humboldt rejected those claims outright.

For Humboldt, nature was interconnected but not deterministic. Climate, altitude, flora, and geography shaped societies, but they did not dictate their political or moral outcomes. He disputed the idea that tropical environments produced despotism or inferiority, insisting that empirical observation showed no such hierarchy. This was a direct challenge to the pseudo-scientific logic that had long been used to justify empire and slavery.

What Wulf makes clear is that Humboldt did not specify a political project to Bolívar, but he gave him something more elemental: permission to imagine equality across climates and continents.

That distinction feels relevant again. The question is not whether geography, culture, or history influence political outcomes – they do – but whether we treat those influences as destiny. When power intervenes today under the guise of inevitability, or stability, it echoes an older argument: that some places are perpetually provisional, and some peoples are perpetually not yet fit to govern themselves.

Humboldt’s wager was that this was not a law of nature, but a failure of imagination.

i absolutely LOVE this book